The Origins of Margarine

Margarine was first invented in France by the chemist Hippolyte Mèges-Mouries in 1869. Its creation was in response to a competition launched by Emperor Napoleon III for a cheap alternative to butter, which the Emperor specified was to be a “fatty substance similar to butter, but less expensive, capable of keeping for a long time without deteriorating in its nutritional value.” In an era when butter was in short supply, relatively expensive and not preserved in chilled storage, the Emperor envisaged a “product capable of replacing butter for the navy and for the less well-off social classes.”

This original margarine invented by Mège-Mouriès differed from modern margarine mainly in that its major constituent was animal fat rather than vegetable oil, the latter becoming characteristic of margarine in the early 20th century. Margarine was a white rather than yellow substance, like butter. The original white emulsion was a mixture of beef fat, milk and water, labelled “margarine” (or ‘oleo-margarine’ in the United States), a compound of the Greek márgaron (μάργαρον: “pearl white”) and the -ine suffix of glycerine.

Margarine's invention came at a commercially propitious time. The Franco-Prussian war broke out a year later in 1870 and with it came the collapse of the Second French Empire. The upheaval caused to the agricultural economy by the war drove butter prices sky high. One of the companies most affected was Jurgens, a Dutch enterprise that had established itself as one of Europe's largest butter companies and had a particularly strong foothold in the German and British markets. Its astute owner followed margarine developments with fascination, sensing the potential for leveraging scientific and technological innovation to radically overhaul the butter industry (the Victorian equivalent of what today would be termed 'disruption').

Jan Jurgens visited Mège-Mouriès in Paris in June 1871. He was eager to produce the new margarine on a large commercial scale but was disadvantaged by the fact that the Netherlands did not then have a patent law (the 1817 Patent Act had been repealed in 1869 and a replacement to it would only come in 1910). The exact proceedings of the meeting are unclear but the consensus among historians is that Mège-Mouriès demonstrated to Jurgens how to produce margarine in exchange for a fee. For reasons not easily understood, Jurgens went on to show margarine to another Dutch butter rival from the same town of Oss in North Brabant, a trader by the name of Simon Van den Bergh, who quickly came to overtake Jurgens in margarine production and developed a strong export market in Britain, Belgium and Germany. By 1883, the Netherlands had established itself as Europe’s margarine epicentre and was exporting around 40,000 tons of the white substitute. The Van den Bergh factory moved to the port city of Rotterdam, allowing quick and easy access to imported vegetable oils.

In 1908, facing strong competition from depressed butter prices, as well as a rival Danish butter-turned-margarine company called Monsteds (which had built a large factory in London in 1894), the two Dutch companies came to an agreement to pool their profits - a somewhat tense and unsuccessful agreement which was suspended at the outbreak of the First World War.

Margarine’s reliance on more expensive animal fats was necessitated by the fact that vegetable oils are (unlike animal fats) naturally liquid at room temperature, owing to their typically low saturated fat content. (Exceptions include palm oil and coconut oil, which are high in saturated fat and consequently [semi-]solid at room temperature.) In 1901 the German chemist Wilhelm Normann succeeded in inducing the hydrogenation of liquid fat (combining the fat with hydrogen), which produced solid or semi-solid fat. This was avidly adopted by food manufacturers and by 1910 vegetable fats were replacing animal fats in margarine.

Margarine sales soared during the First World War and then slumped in the interbellum era. The two Dutch companies came to a merger agreement in 1927 in Rotterdam, along with two other margarine firms: Centra, and Schicht's. The merged entity was called Margarine Unie (United Margarine). In 1930 it merged with the British soap company Lever Brothers to form the Anglo-Dutch firm Unilever (the name is a portmanteau of Margarine Unie and Lever Brothers). Unilever - which has since diversified into a global behemoth producing a dizzying array of the most sold consumer goods - thus has its origins in margarine production and retained a split headquarters in London and Rotterdam until it decided to consolidate in London in late 2020. Its food HQ is still located in Rotterdam, over a century after Van den Bergh decided to move his factory there from Oss.

Margarine comes to Ireland

Margarine was patented in Britain in 1871 and its emergence on the British market represented an inauspicious portent of long-term decline for Irish butter exports. In the late eighteenth century, butter was Ireland’s most important agricultural export and Ireland was Great Britain’s largest external supplier of butter. Butter exports stagnated from the 1820s at around 550,000 cwt until the Great Famine (1845-‘52), after which butter exports increased irregularly until they reached about 720,000 cwt in the early 1870s and then declined until the eve of the First World War.1 Irish butter sales to Britain were challenged on two fronts: the advent of much cheaper margarine and soaring competition from France and Denmark. French butter had begun to outcompete Irish butter on the London market by the 1870s, which contemporaries tended to attribute to the fact that the cheaper Irish ‘farm butter’ (as distinct from more expensive Irish ‘creamery butter’) was traditionally heavily salted and of varying quality. Salted Irish butter was less in accordance with the English palate than the lightly salted butters emerging from Normandy, where producers had adopted cutting-edge Dutch blender technology, allowing them to buy fresh lumps from farmers a few times a week and mix it in agreeable proportions. Meanwhile in Denmark spectacular gains in both efficiency and quality resulted from the cooperative creameries which spread rapidly from the 1860s. These creameries meant that the separation and churning of butter moved from the farms into centralised cooperatives, where it was performed by machinery. Danish farmers gained another competitive advantage against their Irish rivals by effectively extending the butter production season into winter by feeding cattle indoors on roots and colza cake.

Reflecting such formidable competition, Ireland’s share of the British butter market shrank from 37.8% in 1865 to just 22% in 1890 whilst Denmark’s share increased eight-fold.2 With regards to overall sales of butter, it has been estimated that about 50% of Irish butter’s decline in sales between 1881-‘87 was due to competition from margarine.3 These trends established in the late nineteenth century were to cast a long shadow and permanently shape the British butter market for the next sixty years. Ireland would never recover her erstwhile dominance on the British butter market and even today Irish butter is not remotely as popular in Britain as it is in the United States, where Kerrygold succeeded in establishing a strong foothold and has become the second most sold butter brand.

How the dairy industry responded to margarine

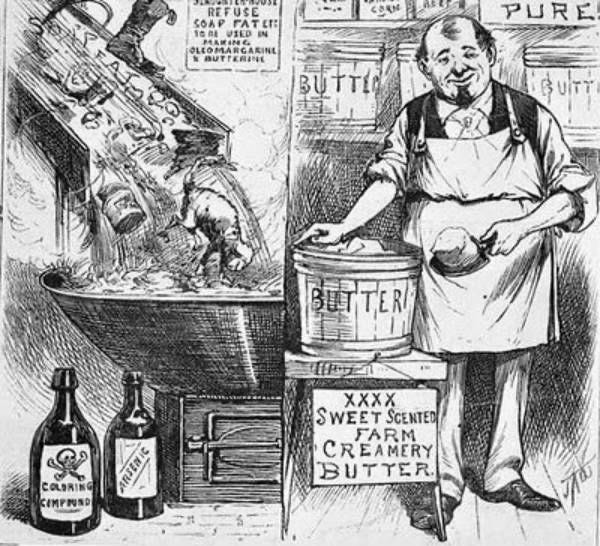

The dramatic commercial success of margarine in the 1870s quickly led to a backlash from threatened dairy interests in Europe and North America. In the United States, lobbying from concerned farmers led to the passage of the 1886 Oleomargarine Act, which imposed a 2 cents per pound tax on margarine and required producers to obtain expensive annual licences. The Act was subsequently amended to ban the common practice of margarine manufacturers dyeing margarine yellow to render their product more visually analogous to butter, a restriction which creative traders circumvented by supplying customers with yellow dye so they could dye it themselves. Several states banned margarine outright. Governor Lucius Hubbard of Minnesota lamented that “the ingenuity of depraved human genius has culminated in the production of oleomargarine and its kindred abominations.” The state of New Hampshire required that margarine be coloured pink, until the law was struck down by the Supreme Court in 1898.

In the then United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, the anti-margarine cause was enthusiastically taken up by Irish politicians and farming associations. ‘Butterine’ - margarine admixed with small, varying proportions of butter (a sort of nineteenth century prelude to the ‘spreads’ of the 1990s) - was a source of acute concern. It gained traction among the English working class and was reportedly selling double the quantity of Irish butter in London. Traders of butterine often copied the exact colour, shape and wrapping of Irish butter. It became common for butterine to be sold as pure butter, the market incentive being that traders could gain a higher profit by buying butterine, which was much cheaper than butter, and selling it for the same price. By 1885 Cork butter exporter W.J. Lane attributed his industry’s woes more to “the produce of the butterine factories than to the butter shipped from France, Denmark, Germany and Sweden.”4 The Irish media railed against the fraudulent tactics of the butterine peddlers. The Cork Examiner in an editorial expressed outrage that British customers were being inadvertently duped by dishonest labelling and protested the displacement of Irish butter to counterfeit imitations:

This roguish compound is beating Irish butter out of the market. While our farmers are making earnest efforts to improve the make, they see the price tumbling under the competition of this specious rival. This is not a question of free trade or protection. What is asked in the interest of the Irish maker is simply that when fat is sold it shall not be permissible to represent it as butter.5

In 1887, six Irish MPs representing dairy constituencies (one of whom was a former Cork butter trader) introduced a bill in the British Parliament with the aim of banning the adulteration of butter, suppressing misleading margarine marketing and ensuring customers purchasing margarine were conscious of their purchase and had not been inadvertently misled by deceptive labelling. It was an uncommon point of agreement between the Irish nationalists and the ruling British Conservative government of Lord Salisbury, which was close to landed interests. On 1 January 1888, the Margarine Act came into force (still on the statute books in the Republic of Ireland). To protect consumers against deceptive trading tactics, the legislation prescribed strict protocols for the sale of margarine. Margarine (which the act defined as 'substances, whether compounds or otherwise, prepared in imitation of butter, and whether mixed with butter or not') was to be sold explicitly labelled as margarine and, to avoid any potential misunderstandings, the margarine was required upon purchase to be placed in a paper wrapped with ‘margarine’ in capital letters.

Every package, whether open or closed, and containing margarine, shall be branded or durably marked “Margarine” on the top, bottom, and sides, in printed capital letters, not less than three-quarters of an inch square; and if such margarine be exposed for sale, by retail, there shall be attached to each parcel thereof so exposed, and in such manner as to be clearly visible to the purchaser, a label marked in printed capital letters not less than one and a half inches square, “Margarine”; and every person selling margarine by retail, save in a package duly branded or durably marked as aforesaid, shall in every case deliver the same to the purchaser in a paper wrapper, on which shall be printed in capital letters, “Margarine.”

The Act also required that manufacturers of margarine be registered with the local county councils:

Every manufactory of margarine within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland shall be registered by the owner or occupier thereof with the local authority from time to time in such manner as the Local Government Boards of England and Ireland and the Secretary for Scotland respectively may direct, and every such owner or occupier carrying on such manufacture in a manufactory not duly registered shall be guilty of an offence under this Act.

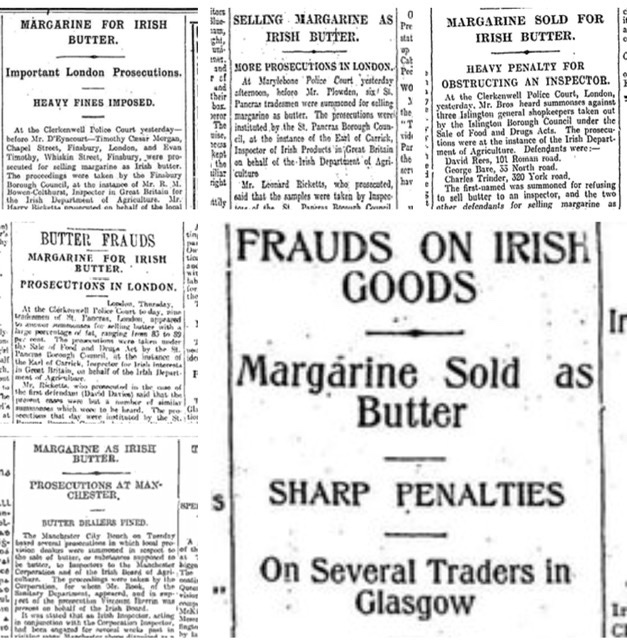

The Act seems to have been initially enforced more strictly in Ireland (where farming concerns were more predominant) than in Great Britain, where the practice was undoubtedly more widespread. In 1898 there were 35 prosecutions for illegal sales of margarine in Dublin alone, all of them resulting in convictions. By contrast in much of working class London and Glasgow, the law was a dead letter and margarine fraud proceeded apace with apparent impunity. In the years subsequent to the Act’s passage, Irish MPs often denounced the laxity of the Act’s enforcement in Great Britain and the failure to take action against those who sold margarine as Irish butter.

Hugh Barrie, unionist M.P. for Derry North, bemoaned widespread non-compliance in Glasgow with the Act and urged the Secretary for Scotland to take action against deceitful traders selling fake Irish butter:

I beg to ask the Secretary for Scotland whether he is aware that the Margarine Act is so inefficiently administered in Glasgow that unlabelled margarine is exhibited with impunity in numbers of shop windows throughout the city, ticketed in such a way as to lead the public to believe that it is Irish butter, and is also sold by these shopkeepers as butter and in parchment not bearing the word margarine; and whether he will take steps to put a stop to these practices.

His complaint reflects a central defect in the Margarine Act: enforcement was largely devolved to local authorities. Safeguarding the commercial integrity of Irish butter could only be but a peripheral preoccupation for large urban municipalities in Great Britain.

Denis Kilbride, a nationalist MP for South Kildare, introduced a bill in parliament to tighten the law and require more strenuous enforcement. Meeting in Belfast in 1909, the Irish Creamery Managers Association passed a resolution urging support for the bill as necessary for suppressing fraudulent trading of margarine and protecting the consumer’s right to choose:

That the Bill recently introduced by Mr Kilbride M.P. to prohibit the colouring of margarine so as to resemble butter, has our hearty approval, as from the numerous reports of prosecutions in the weekly trade papers, it is quite evident that the Irish butter trade suffers severely in England owing to the gross frauds which are perpetrated on the public by the dishonest sale of margarine as butter. It is our belief that the consumer, instead of objection, will only welcome a law which will enable him to purchase margarine in a form in which he can easily identify it from butter. We regard the present safeguards as inadequate, and request the County and District Councils and all public bodies to give Mr Kilbride all the support in their power.6

The Irish Department of Agriculture leads the charge

On the recommendations of Sir Horace Plunkett’s 1896 Recess Committee report, the British government established in 1900 a new devolved Department of Agriculture and Technical Instruction in Dublin to take charge of the administration of Irish agriculture. Plunkett, then unionist MP for South Dublin, had pioneered the Irish agricultural cooperative movement and became vice president of the new Department (a position of de facto leadership since the Chief Secretary to the Lord Lieutenant was ex officio president). Plunkett had urged a course of moderation in the drafting of the Margarine Act, arguing that restrictions on margarine must not be actuated by a petty desire to suppress competition but rather concern itself mainly with protecting the rights of customers.7 He advocated fines on fraudulent traders as a means of making unrumerative “the fraud upon producers and consumers through the sale as butter of substances made from fats other than butter fats.”

The central flaw of the Margarine Act was that the enforcement of its provisions was devolved to the local authorities. The interests of Irish dairy farmers were necessarily not an overriding priority for councillors in London or Manchester and they had little economic incentive to spend money on mass inspections. Irish butter needed an active champion and the new Department in Dublin filled this lacuna.

The Department viewed its role in terms of promoting Irish agricultural interests and protecting Irish farmers. It led a crackdown on traders in Britain selling fake or adulterated Irish butter, which the Department believed ‘was carried on to a scandalous extent’. This campaign was led by Charles Ernest Alfred Somerset Butler, Viscount Ikerrin and Earl of Carrick, and particularly by his energetic inspector R.A. Whyte, who conducted spot checks on hundreds of traders throughout the cities of Great Britain. Lord Ikerrin was a scion of the Butler family, an old Norman family which had played an extremely powerful role in Irish political history since the Norman invasion in 1169 and leading members of which had been representatives of the kings of England in Ireland throughout much of the middle ages (the surname stems from the 12th century progenitor of the dynasty, Theobald, who was given the king’s hereditary position as 1st Chief Butler of Ireland). Unlike his boss Horace Plunkett, Lord Ikerrin’s agricultural experience was limited, but like his boss, he came from an old powerful Norman family and was an advocate of what was then called ‘constructive unionism’ (or ‘Killing Home with Kindness’), a movement of Edwardian unionists eager to demonstrate that Irish grievances could be satisfied within the ambit of the union. (A devolved Department of Agriculture can be seen as a kind of sop substitute for a Home Rule parliament - agriculture then dominated the economy of Ireland outside Belfast so it was an important institution of power.) He and his team were tremendously successful in their campaign and their achievements were lauded by the Irish media. The Irish Independent hailed Lord Ikerrin and welcomed the deterrent effect of the prosecutions:

Viscount Ikerrin is certainly justifying his appointment by the Department of Agriculture to look after the interests of Irish farmers in England. That there was ample necessity for the appointment is proved by the number of prosecutions which he has successfully instituted in cases of foreign and adulterated produce being palmed off on the public as Irish...Quite a number of English shopkeepers have found to their cost that it does not pay to sell margarine for Irish butter…The most recent cases in Wigan were most glaring, and now in Manchester another crop of prosecutions for selling margarine as Irish butter has been reaped by Lord Ikerrin and his inspectors. The greater activity they display the better it will be for Irish producers and honest English shopkeepers.8

Whyte, who conducted hundreds of the spot checks, justified the campaign in terms of consumer protection and defending the interests of Irish farmers against unscrupulous traders. In a speech to the Certified Institute of Grocers in Nottingham, Whyte lamented the fall in Irish butter exports to Great Britain and deplored the deceptive mechanisms used to sell margarine. He acknowledged that margarine was potentially ‘a useful article of food’ and believed that ‘under a properly organised system there should be no conflict between the margarine and butter trades.’ He centered his objection to the margarine trade in the deceptive means it employed rather than the substance it sold. There was never any question of the Department seeking to ban margarine or restrict its availability, as in many American states. Free trade and commerce were too deeply ingrained into Edwardian political culture for such a proposition to be realistic, even ignoring the limited scope of the Irish dairy industry’s ability to exert influence over a British parliament increasingly orientated to the newly enfranchised urban, industrial working classes (who welcomed the option of a cheaper food).

To give a flavour of how a Department spot-check was conducted, the following is from a 1914 news report on a court prosecution pursuant to one:9

Francis David Doyle, assistant inspector for the Irish Department of Agriculture, stated that acting on the instructions of Mr. Bowel-Colthurst (Inspector in Great Britain for the Irish Department of Agriculture), he visited the defendant Morgan’s shop, and acted there as agent for Inspector Fowler, who is food and drugs inspector to the Finsbury Borough Council. Witness said he was served by a lady assistant. When he asked for a quarter of a pound of Irish butter he was given a substance resembling butter, which was wrapped in a plain wrapper. He handed the sample to Inspector Fowler, and subsequently it was analysed. At the time of the visit to the shop he was disguised as a working man. Proceeding, witness said he had been making purchases at the same shop since December of last year. Each time he was served with a substance other than Irish butter and in each case it was wrapped in a plain wrapper. On the last occasion he paid threepence for a quarter of a pound of the substance.

Cross-examined by Mr. Jenkins, for the defence, witness denied that the assistant told him she had no shilling butter in stock, the cheapest being 1s 1d, nor did she say that she had got margarine at 1s.

A butter expert in the employment of the Irish Department of Agriculture stated that factory Irish butter could be purchased in January last at about 106s a hundred-weight. It was a recognised shilling a pound article. The best creamery butter was quite different in appearance and cost about 10s a hundred-weight more. Margarine, he added, cost about half the price of the factory Irish butter.

Inspector Fowler stated that the sample contained 80 per cent. of margarine.

The young lady assistant, called for the defence, stated that she told Mr. Doyle she had no shilling butter in stock and that the cheapest was 1s 1d a lb.

The magistrate remarked that it seemed to him a most deliberate case, and that there was absolutely no excuse for it. The defendant was fined £18 and 12s 6d costs.

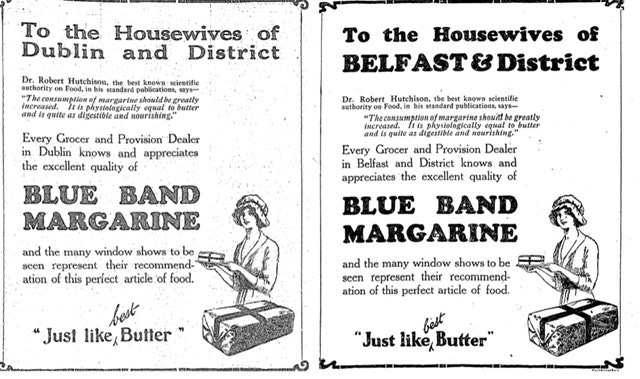

Margarine as a household good

As a result of the Department-orchestrated prosecutions, the problem with adulterated butter or missold margarine seems to largely fade as a significant issue by the eve of the First World War. From then on, most people buying margarine were purchasing it in conscious knowledge that it was actually margarine, usually because of wartime scarcity (during the First and Second World Wars), its lower price or (from the 1960s) concerns over the comparatively high saturated fat content in butter. Margarine has never held a competitive advantage against butter on the grounds of its flavour. That margarine companies consistently advertised their margarine brand as tasting similar to butter (from the post-WWII Stork advertisement above assuring customers Stork tastes so good they won’t be able to believe it’s margarine to ‘I Can’t Believe It’s Not Butter’ launched in the 1980s) is an implicit acknowledgement of the fact that margarine was popularly perceived as distinctly and definitely inferior in taste relative to butter.

During the First World War, consumption of margarine skyrocketed due to butter shortages. In the entire United Kingdom in 1919, 345,000t of margarine were consumed, more than twice the amount in 1913 (excluding supplies for the military).10 But, as would later occur during the Second World War, consumption declined rapidly when restrictions were dropped and butter became available for purchase again.

Partition and Independence: how they affect the margarine market

Two new political entities on the island emerge in the early 1920s: Northern Ireland (consisting of 6 counties in the north east) and the Irish Free State (26 counties in the rest of Ireland), the former remaining in the UK, but with a new home rule parliament controlling both agriculture and the economy, whilst the latter was established as an effectively autonomous Dominion in the British Empire and progressively transitioned to becoming an independent republic. The all-Ireland Department of Agriculture gave way to two separate Departments of Agriculture in the two new jurisdictions.

The Irish Civil War placed huge strain on the finances of the nascent Irish Free State, public spending doubled during the war. The new Minister for Finance Ernest Blythe had to deal with a budget of only £8m even though the national debt was £6m. Consequently, the 1920s were characterised by severe austerity (the 1924 budget infamously reduced the old age pension by 1 shilling) with little money available for hospitals and other public institutions. This provided a financial inducement for some institutions and households to switch to margarine from butter. This often provoked considerable controversy and dissent.

An example of such a controversy is the dispute at Waterford County Hospital, which in 1928 replaced butter with margarine to save on food expenses. Butter cost 1/7 per lb compared to only 5d per lb for margarine: the latter was bought locally from McDowell’s Margarine Company (which had established a margarine factory in 1912 in Waterford city to service customers in continental Europe and the British Empire). The switch was motivated primarily by cost considerations but there had been no consultation with patients and the move aroused great upset among both staff and patients. At an emotive committee meeting a few weeks later to discuss the change, the Medical Officer, Dr V.J. White submitted a report defending the replacement of butter with margarine, contending that there was little difference in either the fat or protein content nor the overall calories that margarine provided relative to butter. (Knowledge of the fat-soluble vitamins was still somewhat in its infancy in 1928.) He argued that margarine was produced ‘under the most sanitary conditions, is now a stable fat food and contains the same nourishing qualities of butter and is sold at a price about one half that of butter.’ He asserted margarine’s nutritional equality with butter and pointed out its widespread international acceptance:

The margarine we produce here at our very doors in Ireland is practically, from every respect, from a food, health giving and body-building viewpoint, absolutely identical with the best butter. We here in Ireland do not and have not used margarine to anything like the extent which the other nations, European and American, use it.

The other committee members did not dispute his defence of the health properties of margarine. They did however complain that it had been a decision imposed on patients with no consideration of their wishes and complained of the unhappiness it had provoked.

Nurse Ms Whelan testified that patients were refusing the margarine:

I know the patients here and they will not eat it. I have seen them eat dry bread and in some cases prefer to go hungry than use margarine.

Another committee member, Mr Dea, spoke out in favour of personal choice:

I hold that if a patient prefers butter to margarine that patient should get the butter not margarine. No matter for what reason if you take a dislike to a food it is not nourishing and it will not be as beneficial if you are forced to eat it as if you ate it with a relish. They will get a disgust at the margarine. The very name sickens them. I saw patients in the hospital and the margarine was good and I questioned them but they said they would prefer the butter to margarine.

A similar controversy arose at Belfast Workhouse in the 1920s but in this case the doctors championed the butter cause. Belfast Workhouse is nowadays reputed as a kind of Dickensian institution which somehow survived into the 1930s; it still housed thousands of men, women and children in the 20s. During the First World War, the Workhouse had switched to margarine due to war scarcity, following the lead of their counterparts in Newry and Waterford. By 1929, the Board of Guardians (infamous for their penny pinching) had done a u-turn on margarine after pressure from the workhouse doctors concerned about the lack of vitamins in margarine. An Irish Times report from 1929 summarises the arguments advanced.

The back to butter campaign in the Belfast Workhouse is proceeding daily and provides a good deal of diversion for the community. The Guardians, who have been notorious for their parsimony in the granting of certain forms of relief, are now accused of extravagance by the Home Office because they desire to give butter instead of margarine to the inmates of the institution. The Ministry declares that, according to its medical experts, margarine is good enough for adults, and that the absence of vitamins makes no difference, whereas the Workhouse doctors are of a contrary opinion. The different in cost would mean £1,000 additional charge on the rates but it is pointed out that the money would be paid to local farmers, while in the purchase of margarine it would be sent out of the province...In view of the Ministry's assertion that vitamins of butter absent in margarine are of no importance to adults, a question put by Mr Nixon, an independent Unionist, is of interest. He asked if the medical advisers of the Ministry had examined the inmates prior to the order in reference to margarine and was informed by Sir Dawson Bates that that would be a physical impossibility. "I thought so," said Mr. Nixon. "A great many of these inmates have a very low vitality, due to starvation conditions before entering the Workhouse." That point of view is not sufficiently considered.11

Concern over margarine’s vitamin deficiencies

The Ministry dismissed the comparative lack of vitamins in margarine as of ‘no importance to adults’ because one of the main concerns at the time was the complete absence of vitamin D in margarine, which was the most common factor in the aetiology of rickets. Rickets is a childhood disease (of which osteomalacia is the adult counterpart) that involves weak or soft bones due to insufficient calcification of the epiphyseal plate; without vitamin D, very little calcium is absorbed in the small intestine and brittle bones are the inevitable result. Rickets was extremely widespread among working class children in urban areas prior to the popularisation of cod liver oil (the densest dietary vitamin D source) from the 1930s onwards, mainly due to lack of exposure to sunlight and a diet lower in vitamin D dense foods (i.e. oily fish, eggs and to a lesser extent butter). Milk has a small amount of vitamin D but butter - being a concentrated source of milk fat and thus denser in milk’s fat soluble vitamins - has a modest amount and was used as an anti-rachitic treatment before cod liver oil became widely used.

In 1928 a paper by two Lever Brothers (which joined the merger to become Unilever in 1930) scientists on ‘Butter and Margarine in Relation to Public Health’ was read at University College Dublin. The scientists identified the main advantage held by butter as its superior gustatory appeal relative to other animal fats, along with its density in the fat soluble vitamins A and D:12

(1) In its attractiveness and appeal to the palate.

(2) In its richness in the fat-soluble vitamins A and D.

While few people objected to cream, ice-cream, butter or bacon fat, quite a large proportion shied at the thought of fat pork, beef or mutton…It was when the relative richness in vitamin A and D was considered that butter was seen to stand out not only in contrast to normal margarines but also in contrast to all ordinarily eaten animal or vegetable fats. Butter always had been the average person's main source of supply.

The scientists envisaged several ways of compensating for the lack of vitamins in margarine. They floated the possibility that those eating it could be advised to double their milk and egg consumption, which was understandably discounted as unrealistic. Fortification with vitamin A and D was envisaged as the best means of making margarine nutritionally equivalent to butter but technology at the time meant this would have involved mixing margarine with fish oils, which might further detract from margarine’s taste and sharpen the distinction with butter.

The impact of World War 2 and rationing

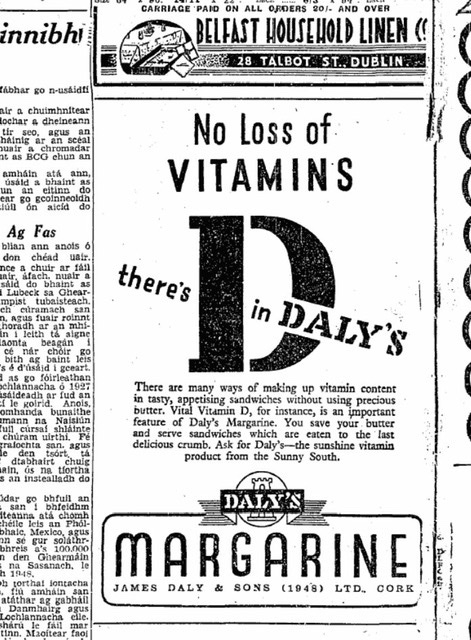

In 1940, with the breakout of World War 2 and a scarcity of butter, the British government opted to oblige margarine manufacturers to fortify margarine with vitamins A and D. The Irish government did not follow suit due to comparatively low margarine consumption but domestic manufacturers tended to voluntarily fortify their products anyway to continue selling to the British market. Margarine advertisements in the newspapers thenceforth often stress the vitamin D content in margarine to dispel concerns about its nutritional inadequacy, such as this ad below in 1948 for Daly’s Margarine (Daly’s Margarine was the predecessor of Dairymaid spread - this is incidentally an example of margarines transitioning into nebulous ‘spreads’ in the 80s and 90s).

The outbreak of World War II brought a severe crisis for Ireland’s agricultural economy. The country pursued a course of neutrality during the war and the British government rapidly turned off its exports tap. 6m tons of animal feed had been imported from Britain in 1940 but this dropped to 0 by 1942; imported fertiliser likewise fell to nothing whereas it had been 74,000 tons in 1940. The absence of vegetable oils forced Irish margarine production to cease in 1942 and it would not be revived until the end of the war. Butter production was always concentrated in the south-west of the country but it became uneconomic with the war due to the diversion of farms to tillage, the greatly increased cost of transport due to fuel shortages and the collapse of feed imports. A flourishing black market took place and creameries began exporting to Great Britain, where butter could command higher wartime prices. The dearth of butter in Dublin was lamented in the following complaint from 21 April 1942 by Labour Party politician Dr Joseph Hannigan:

I am sure the Minister is aware that a very serious situation has arisen in Dublin on account of the butter shortage. Butter has practically completely disappeared from the shop windows. We have now not alone the depressing spectacle of bread queues, but the spectacle of butter queues as well. Bread and butter queues in the capital city of the country are a sad commentary on the Government Departments responsible for food production and supplies.

Rationing of butter in Dublin was introduced later that year in October and extended to the entire country on 5 June 1943. The shortage of butter had baleful implications for children’s bone health. Overall per capita daily intake of vitamin D fell from 1.9 μg in 1940 to 1.5 μg in 1942, the fall being concentrated among the urban working class. Rickets rapidly grew rife in Dublin. The number of children admitted to radiological departments of children's hospitals more than doubled between 1939-40 and 1941-2.13 Although World War II ended in 1945, rationing only came to an end in Ireland in 1951. During the ‘Great Freeze’ of 1947, butter again became very scarce and there was increased reliance on margarine. Senator William Fearton, Professor of Biochemistry at Trinity College Dublin, deplored the fall in butter rations to two ounces and was sceptical about the ability of standard fortification to render margarine nutritionally equivalent to butter:

I deplore the fall in butter production which has reduced our weekly ration to two ounces. For our survival, we require calories to form heat, nitrogen and proteins and a small amount of fat. The optimum figure accepted by world authorities is about three ounces per day per person and the minimum one ounce. If you do not get that amount of fat in the day then your own fat reserves are gradually deleted, and along with that various other unfortunate things happen. I think it is the primary duty of the Government to see that we, the people of this State, receive our one ounce of fat in the day —that means 100 tons of fat per diem for the maintenance of the country. It seems a lot, but it has been obtained in the past and I hope it will be obtained in the future. What has happened is that there has been a shifting over with a gradual decrease in the amount of butter fat available to us, supplemented by margarine. I think that we are approaching danger level…In addition, we have a supply of margarine. The amount to me is unknown, but I presume we shall be able to find it out. That margarine is of two grades and the difference in the grading quality to me is unknown. One must, however, remember that margarine lacks various essential things which butter has, and that, though it is possible to doctor margarine and to reinforce it in various ways, it is an expensive business, if you are to do it properly so that supplementing the fat ration by margarine is a matter which requires a great deal of consideration. Having, as it were, put the fat in the fire, I have nothing more to stress.

Margarine in the post-war era

Butter production quickly recovered and rations became progressively more relaxed, until they were abolished altogether in 1951. In the short term margarine consumption collapsed with increased butter rations. In 1948 daily per capita consumption of butter reached 46.4g whereas margarine fell to 5.7g. Margarine became associated in Ireland for decades with wartime scarcity and poverty, which tended to reinforce the superiority of butter in the popular mindset.

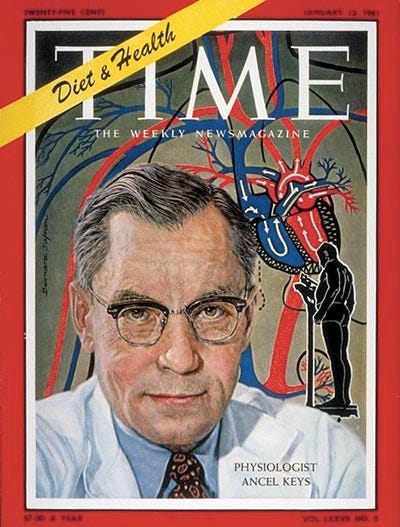

Before the 1960s, price was margarine’s only real appeal, nobody disputed its inferior flavour relative to butter. From then on and especially with the 1978 publication of the controversial Seven Countries Study (directed by American epidemiologist Ancel Keys) medical opinion throughout the western world shifted towards associating saturated fat intake with increased risk of heart disease. Margarine was portrayed as a healthier choice by governments and doctors because of its low saturated fat content. Margarine’s health image would last until the early 90s, when scientists found a strong association between margarine and heart disease due to the trans fats created artificially with the partial hydrogenation of vegetable oils used in margarine.

With Ireland’s strong dairy tradition, margarine never became as popular as elsewhere, though its consumption did increase in the subsequent decades. Intake rose from a per capita daily consumption of 6.5g in 1954 to 8.6g in 1960. In the early 1980s, margarine’s share of the combined butter-margarine market had risen to 31% but this was still the second lowest in the 10 EEC countries, just behind Ireland’s fellow butter-lovers in France:14

France - 30%

Ireland - 31%

Italy - 40%

West Germany - 53%

UK - 57%

Belgium/Luxembourg - 57%

Denmark - 63%

Greece - 74%

Netherlands - 82%

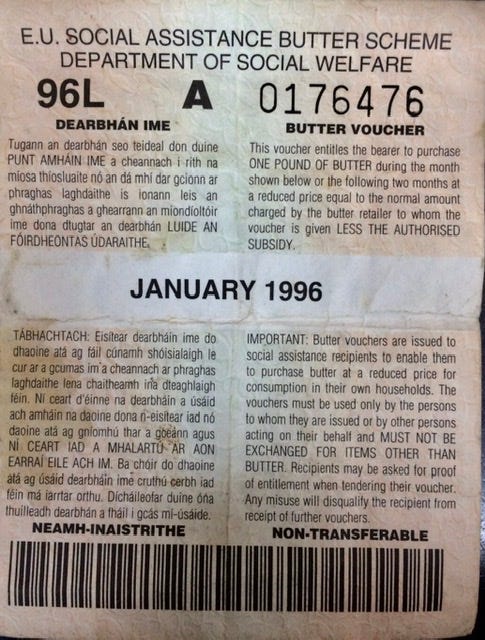

The Irish government was considerably more reluctant than its international peers to encourage the public to switch to margarine, mainly due to butter’s importance to the economy. In 1978 the government began a social assistance butter scheme, which lasted until 1999, and subsidised the price of butter for social welfare recipients. This was attacked on health grounds throughout the 1980s. The Consumer Association of Ireland accused the government of subsidising heart disease.15

Margarine manufacturers focused on respected health bodies and used their enormous financial resources to co-opt them into promoting their products’ supposed health properties. The Irish Heart Foundation led the margarine charge early and other health charities quickly followed its lead, such as the Irish Cancer Society, which said in 1976: “we are now promoting margarine instead of butter, like the Irish Heart Foundation.”16 Sponsorship of the Irish Heart Foundation by Flora margarine, then owned by Unilever, drew strong criticism from the country’s leading heart surgeon Maurice Neligan, who held it was an inappropriate conflict of interest and said it ‘was farcical to suggest that margarine is better for you than butter’. In a letter to the Irish Press, Tom O'Dwyer, president of the Irish Creamery Milk Suppliers' Association (ICMSA), echoed these criticisms, which he said “raised serious question marks once again about such health claims, explicit or implied.”17

The pro-margarine bias of the Irish media was regularly criticised in the 70s by farmers. That there was an urgent health imperative to substitute butter with margarine was taken as axiomatic by journalists and remained unquestioned wisdom until the trans fats scandals and the reassessment of saturated fat in the 1990s.

Margarine morphs into spreads

By the 1990s margarine’s health aura came under attack with new epidemiological studies showing a link between trans fats and heart disease. In 1993, a Harvard study showed a 70% increase in the risk of heart disease for women who consumed margarine and estimated that 30,000 annual deaths from heart disease in the US were linked to it. Margarine was especially high in trans fats because at that time the vegetable oils were all partially hydrogenated. Trans fats were felt to be atherogenic because they tend to both increase an individual’s LDL cholesterol (like most forms of saturated fat) whilst simultaneously lowering HDL cholesterol (unlike saturated fat). Many consumers were perplexed that a food which the health establishment had championed for decades was now actually shown to contribute significantly to heart disease. Heart health had also been central to margarine advertising and this started to become untenable. In 1992 the Irish Director of Consumer Affairs directed Flora to cease using the expression a “heart healthy alternative” and threatened the company with prosecution in 1995 over its TV advertisements promoting margarine as a health food.

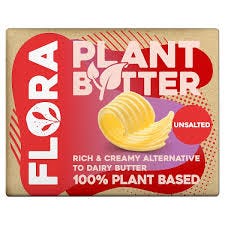

The controversy over margarine did much to injure its healthy reputation. Such has been the damage to margarine’s public image, one will struggle to find any product labelled ‘margarine’ in even a large supermarket. It is usually sold either by pretending it’s a ‘baking block’ or some ‘spread’ variant of butter.

‘Spreads’ became popular in the 1980s for practical, price and taste reasons (relative to classic margarine). Generally they consisted of mostly vegetable oil and water, with the industrial taste diluted and rendered more palatable by the addition of small amounts of cream - as in more expensive spreads, like Dairygold - or, more commonly, buttermilk (usually reconstituted). Although salted butter does not generally require refrigeration, modern food culture is shaped by often exaggerated food safety fears and the butter dish (which stored butter at room temperature) has become a much rarer sight in Irish kitchens. Many customers are now habituated to refrigerating virtually all food products; this makes spreads a more practical choice for such people as spreads are easily spreadable on bread when they are refrigerated, unlike butter.

Spreads cost less than butter because vegetable oil, their main constituent, is much cheaper than milk fat. This provides a higher profit margin for the company, especially when they succeed in appropriating butter’s iconography and tantalise the customer into paying a higher price by training them to conflate their ‘spread’ product with real butter. This is achieved by deceptive advertising, such as including ‘butter’ or related adjectives in the titles of their products, by using yellow colouring to conjure images of butter and by claiming to be ‘buttery spreads.’ The use of ‘buttery’ adjectives allows them to circumvent consumer protection law which restricts the label ‘butter’ to products made from over 80% milk fat. Margarine manufacturers carefully circumvent consumer protection law and even use it to further confuse consumers. Margarine is a label restricted to products made with at least 80% oil. Stork (which was the main margarine brand in post-war Britain) now describes itself as a ‘baking block’ and has cleverly formulated its ingredients to just under 80% fat so that supermarkets can’t label it with the consumer-repelling label ‘margarine.’

A more audacious example is Flora’s Plant B*tter, which deliberately substitutes u with a leaf to elide the name restriction (in the United States, which has no such law banning fake butter, it is openly labelled ‘Flora Plant Butter’) and has a fat content of exactly 79%, to preclude supermarkets labelling it in their shelves as margarine.

Spread manufacturers have so successfully blurred the distinction with butter that many, if not most people, will refer to common spreads like Dairygold as ‘butter’, even though Dairygold is mostly composed of palm oil, rapeseed oil and water. Any deli counter in Ireland will invariably ask customers if they want ‘butter or mayo’ on their sandwich, the ‘butter’ used is invariably spread (and usually a far cheaper variant than Dairygold). In asking its readers if they prefer to ‘keep the lid on their butter’ or dispose of it, TheJournal.ie illustrates how confusion over the distinction affects even media outlets.

Big Margarine conquers Irish dairy

Spreads rapidly and successfully supplanted butter in the 1980s. By 1991 spreads (19,100 tonnes) were selling considerably more than butter (13,600 tonnes). In the late 80s the Irish Dairy Co-Ops were promoting 'spreads' in their advertising and this was furiously denounced by the ICMSA, which blamed it (somewhat exaggeratedly) for the fall in butter consumption from 35,000 tonnes in 1985 to 13,000 tonnes by 1989. Tom O’Dwyer of the ICMSA railed against ‘spreads’ and the dairy industry’s suicidal promotion of them:18

By importing vegetable oils we are suffering a net loss of 15,000 tonnes in butter consumption. The same is happening on the Continent and in the UK where pure butter consumption is down by 50% this year. There is no independent research to substantiate the present 'butter is bad' syndrome - for the most part, research is funded by the margarine companies who have a vested interest in the promotion of vegetable oil and as a result are misleading the public. Given that these research findings are biased and the fact that our technology can process butter into a spreadable form, we are demanding that the dairy industry redirect its research and marketing to the promotion of Irish butter instead of foreign oil.

His successor Con Scully would express similar sentiments:

While the farming community as well as any other sector welcomes diversity on our supermarket shelves surely there is something intrinsically wrong with our dairy industry if our own pure dairy products are being undermined by sophisticated marketing for ‘dairy’ spreads…The onus is on the Board members of our co-ops to prove that their loyalty is first to the farmer suppliers. When we consider that £1.1m was spent in 1990 on media advertising for ‘dairy’ spreads, compared to £450,000 on butter advertising, it is obvious that something is amiss….It is in relation to demand that the problem exists for butter. The large margarine companies have invested heavily in telling us that margarine is the healthier option, while there has been no objective analysis of the health benefits of butter. There the public response has been in favour of more attractive product - as directed by the marketers.

From the 1870s onwards, Irish dairy interests waged furious campaigns against both butterine and margarine. Margarine posed a real menace to customers and the dairy industry by its unfair and unscrupulous marketing practices. Irish creameries and farmers, through their political representatives, forced the British government into protecting the right of butter customers not to be deceived into purchasing margarine by fraudulent advertising. There is no equivalent campaign today. Margarine and its ‘spread’ progeny mislead the public with impunity and this now raises no objections from industry groups. The main reason for their silence lies in the fact that the dairy industry is now concentrated in just a few companies, most of which produce spreads and butter. These companies can obtain a higher return on spreads, so they have no incentive to defend butter’s integrity against the onslaught of bogus substitutes from which they profit.

The Kerry Group is one such example. It has a position in the Irish dairy market analogous to Kraft in the United States. Kerry’s Low Low Spread claims to be “made from Irish butter milk” but ‘reconstituted buttermilk’ actually makes up just 3% of the ingredients. The main ingredients are sunflower, palm and linseed oils, along with some water. It also features a milk churn and separates the compound word buttermilk - all to reinforce its bogus pretence to be a dairy product.

Misleading advertising cheats both the customer and the farmer. The customer is misled into buying a product by means of deceptive representation. Farmers obtain a lower price for their milk because demand is artificially lowered by unfair competition. It is entirely understandable that Big Margarine resorts to fraud to enrich itself. It has always done so. That the injured parties remain passive victims seems rather more inexplicable, especially when one compares their inertia to the robust response of their ancestors.

Solar, Peter M. “The Irish Butter Trade in the Nineteenth Century: New Estimates and Their Implications.” Studia Hibernica, no. 25 (1990): 136.

Lampe, Markus, and Paul Sharp. “Greasing the Wheels of Rural Transformation? Margarine and the Competition for the British Butter Market.” The Economic History Review, no. 67 (2014): 774.

ibid.

Donnelly, James S. “Cork Market: Its Role in the Nineteenth Century Irish Butter Trade.” Studia Hibernica, no. 11 (1971): 155.

Cork Examiner, 2 June 1887.

Kerry Sentinel, 26 May 1909.

Irish Times, 6 February 1893.

Irish Independent, 26 September 1907.

Freeman’s Journal, 21 February 1914.

Levene, Alysa. “The Meanings of Margarine in England: Class, Consumption and Material Culture from 1918 to 1953.” Contemporary British History, no. 28 (2014): 150.

Irish Times 21 June 1929.

Evening Herald, 17 August 1928.

Robertson, Iris. “The role of cereals in the aetiology of nutritional rickets: the lesson of the Irish National Nutrition Survey 1943-8.” British Journal of Nutrition, no. 45 (1981): 18.

Irish Farmer’s Journal, 21 February 1981.

Evening Herald, 9 July 1988.

Limerick Leader, 3 July 1976.

Irish Press, 15 May 1995.

Nenagh Guardian, 19 August 1989.

This was a really fascinating article - some laws around the naming of non-dairy products have been introduced in the last couple of years in the US, but IIRC so far have only passed on the state level, mainly in places like Wisconsin